The Popular Resistance to Chico and Cellophil

In the 1970’s, the Anti-Chico Dam struggle of the Kalinga and Bontok people, followed soon after by the Tinggian opposition to the Cellophil Resources Corporation (CRC), sparked off the popular movement in the region in defense of indigenous peoples’ rights.

The Chico Dam would have inundated villages of the people. Meanwhile, the CRC, a paper and pulp processing plant, would have ravaged vast portions of the Tinggian’s ancestral land in Abra and contiguous areas of Mt. Province and Kalinga.

Amid state repression and outright military brutality, leaders and warriors from these affected provinces came forward to register their communities’ desire to be left alone to chart their own course of development and defend their ancestral domain.

Community meetings and bodongs or peace pacts galvanized the people’s solidarity and resolve to fight as one. They were not alone in this fight. Their protest and defiance gained support and admiration from communities and countries near and far.

One of the brave leaders of the struggle was Macliing Dulag of the Butbut tribe, in Bugnay, Tinglayan, Kalinga who articulated his people’s determination not to sell out their patrimony. On April 24, 1980, military troops of the Marcos dictatorship gunned down Macliing Dulag in the dead of night in an effort to intimidate the indigenous opposition. The people refused to be cowed. Instead, Macliing’s death was commemorated with a Macliing memorial yearly thereafter to remember the martyrs who had given up their lives in the struggle. It also became an occasion where Cordillera advocates would come to express their solidarity with the Cordillera peoples’ struggles.

In 1985, April 24 was commemorated as Cordillera Day for the first time. Since then, Cordillera Day has annually been commemorated by the CPA with a regionally-coordinated mobilization and with the participation of a great number of Cordillera advocates. Cordillera Day has since been held in all of the provinces and in many municipalities throughout the region, where organizations and individuals renew their commitment to support and uphold the indigenous people’s struggle for self-determination.

Gains and Lessons from Chico and Cellophil

The Chico and Cellophil struggles were a great learning experience into the reality of indigenous peoples’ rights. During this period, the concept of ancestral land and self-determination were vague abstractions for many. The Chico and Cellophil struggles educated them that this was concrete reality for indigenous peoples.

Chico and Cellophil gave a deeper dimension to human rights, going beyond the narrow definition of individual civil and political rights as defined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, to the collective human rights of indigenous peoples.

The Chico and Cellophil struggles were waged in uncompromising defense of ancestral land and the right to self –determination, or the right of the indigenous communities to freely determine their continued existence as distinct peoples, and the right to freely determine their political status, and their economic, political and socio-cultural development, at a pace which they themselves define.

The unfolding Chico and Cellophil drama ignited dormant Igorot nationalism. Numerous activists and mass leaders espousing their rights as indigenous peoples emerged. The different Cordillera tribes were challenged into the recognition of the pressing need for a greater unity among themselves if they hoped to succeed in the defense of their collective human rights as indigenous peoples. Igorot students and intellectuals put their energies into the more serious discussion and study of what it meant to be indigenous peoples and national minorities.

This increased introspection and self awareness among the indigenous peoples of the Cordillera paved the way towards a pan-Cordillera mass movement, as it marked the shift from spontaneous reaction to conscious and concerted unified action. As the different Igorot tribes and sectors were increasingly exposed to each other in mass meetings, inter-tribal activities and bodong conferences, there was the opportunity for dialogue and mutual sharing and learning. From here, the different groups realized that they shared a common history of national oppression; a common geography and territory – the Cordillera mountain range; a common persistence of their indigenous cultures, albeit in varying degrees; common problems and common enemies.

The heroic Chico and Cellophil struggles also served to inspire and motivate many non-indigenous advocates, in the region, the nation, and abroad, which made it possible to generate broad national and international support to sustain the growing mass movement. There were broad solidarity and advocacy for the popular resistance in the region from academics, environmentalists, church groups, the mass media, NGOs and a wide array of solidarity organizations. The Free Legal Assistance Group of the late senators Diokno and Tañada offered their legal assistance. Anthropologists and academics wrote numerous treatises. Progressive media practitioners provided good press coverage.

Chico and Cellophil brought to the fore the fact that the present-day problems of tribal peoples and indigenous communities are much bigger and more complicated than any faced in earlier historical periods. More concretely, Chico and Cellophil showed the indigenous peoples of the Cordillera that their problems cannot be taken in isolation from the wider Philippine realities, and the incursions of imperialist globalization.

The indigenist romanticized view of tribal society as a static autonomous entity which should be preserved in its pure form was shattered, as Igorots united with as broad an alliance as possible for the defense of indigenous rights. Although the Chico resistance at the start was the spontaneous tribal response to outside threat, it soon positioned itself firmly within the mainstream of the national democratic struggle.

Armed Struggle and the Cordillera Peoples’ Democratic Front

It was during this time in the 1970s that the Cordillera people finally resorted to armed resistance after peaceful methods to seek redress of grievances had proved futile in the face of unbridled militarization. Many were convinced that this was but a logical step for these warrior societies in the defense of their indigenous peoples’ rights.

During this period, many of the finest sons and daughters of the indigenous communities in the region joined the armed struggle of the CPP-NPA. After a program of rigorous social investigation into the general characteristics of the Cordillera region, foremost of which is its particularity that the majority of its population are national minorities and indigenous peoples, the revolutionary movement articulated its program for the Cordillera People’s Democratic Front (CPDF) in 1981.

The 8-point CPDF program included the recognition of the right to ancestral land and regional autonomy as the form of self-determination for the Cordillera. The CPDF was projected as the umbrella organization of all revolutionary forces in the region allied with the National Democratic Front. In truth, it was the revolutionary movement that first articulated the demands of the indigenous peoples for ancestral land and self-determination.

Struggle against the Batong-Buhay Mines

After Chico, the blatant disrespect of the people’s right to their resources would manifest again with the persistence to open the Batong-Buhay gold mines in Kalinga in 1983 through government and corporate collusion. Having learned from the Chico experience, the people in the affected communities once again put up a fierce opposition until 1984 to frustrate the mining company’s operations. Peasants in Tabuk and Isabela and environmental organizations added their voices in protest against the pollution of the Chico River caused by Batong Buhay’s mining operations.

AntiGrand Canao Struggle

It was not long before the popular resistance in the villages in the Cordillera interior found its way into the urban areas. One issue that drew widespread protest from conscientized Igorots was the Ministry of Tourism-sponsored Grand Cañao from 1980-83, which displayed Igorots dancing and singing through the streets to attract the tourist dollar. Opposition to the Grand Cañao became a rallying point for Igorot students and professionals who opposed the commercialization of indigenous culture, and who protested this imposed celebration in the face of the problems of militarization, ethnocide and development aggression confronting the indigenous peoples.

The Grand Canao Festival was held for a couple of years in Baguio City, then was eventually discontinued owing to criticisms and political actions launched by activists.

Meanwhile, cultural presentations with new revolutionary content were staged, utilizing the traditional sallidummay, uggayam, ullalim. Traditional forms of song and dance infused with new revolutionary content from the areas of resistance in the Cordillera interior were popularized. Other cultural forms depicting the people’s problems and resistance were also creatively developed by progressive cultural workers (eg. Kaigorotan).

The Birth of the Cordillera Peoples’ Alliance for the Defense of Ancestral Domain and Self-determination

The popular resistance in the indigenous communities to Chico and Cellophil inspired the formation of a militant mass movement for the defense of ancestral domain and for self-determination in the Cordillera, within the framework of the wider national democratic open mass movement. The decade of ferment led to increased coordination among the growing number of militant organizations. The people learned the value of concerted and unified mass action towards defining the substance and features of a program for self-determination of the indigenous peoples in the Cordillera.

Militant organizations from various sectors, communities and provinces in the Cordillera gathered and united against the state’s non-recognition of their rights, tradition and culture and the growing threat to their land and life. In June 1984, more than 300 representatives from all over the Cordillera region held a People’s Congress in Bontoc, Mt. Province and organized the Cordillera People’s Alliance for the Defense of the Ancestral Domain and for Self-Determination. With 23 organizations as founding members, the CPA became the political center of a steadily growing mass movement that encompassed the countryside and the urban centers. With the organization of the CPA, the mass movement attained an increased level of coordination at the regional and provincial levels.

From 1984-86, the CPA distinguished itself by being at the forefront of the struggle for indigenous people’s rights. It launched many campaigns such as those for Ancestral Land Rights, anti-militarization, Kaigorotan unity, and genuine regional autonomy as the form of self-determination. CPA’s leadership guided the regional mass movement in all its education and organizing efforts to sharpen the concepts of national oppression and self-determination.

Under the Cory Aquino Regime

In February 1986, the dictator Marcos was ousted through People Power. The Cordillera people’s struggle was clearly integrated in the national struggle that victoriously toppled the fascist US-Marcos dictatorship and brought to power Corazon Aquino. The Filipino people, including those in the Cordillera exalted in the new political atmosphere. Expectations were high that with a new government installed into power in the aftermath of a popular uprising, indigenous people’s rights would finally be recognized.

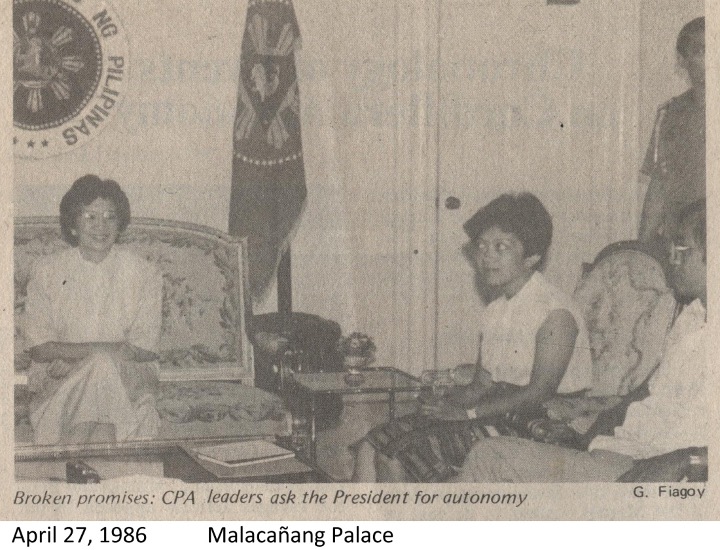

Cordillera Day that year was a big celebration held in Bontoc, Mountain Province. Shortly after Cordillera Day, the CPA had a meeting with President Corazon Aquino in Malacañang on April 29. The agenda of CPA included: 1) the cancellation of Chico and Cellophil; 2) an end to militarization in the region; 3) the return of the lands expropriated from the Taloy folk in Tuba for the Marcos Park; 4) democratic participation in the choice of OICs for the local government units in the region; and 5) the recognition of ancestral land rights and self-determination for the indigenous peoples.

Shortly after Cordillera Day celebration in 1986, the CPA Regional Council had a meeting with President Corazon Aquino in Malacañang. The agenda of CPA included 1) the cancellation of Chico and Cellophil; 2) an end to militarization in the region; 3) the return of the lands expropriated from the Taloy folk in Tuba for the Marcos Park; 4) democratic participation in the choice of OICs for the local government units in the region; and 5) the recognition of ancestral land rights and self-determination for the indigenous peoples.

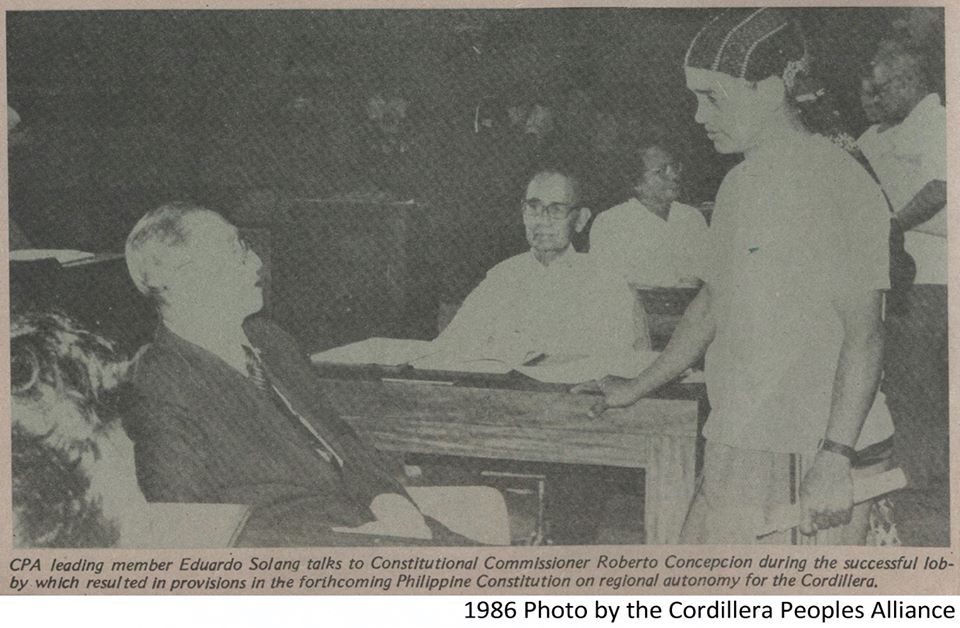

CPA pioneer Eduardo Solang talks to Constitutional Commissioner Roberto Concepcion. CPA mobilized a region-wide lobby of the Constitutional Commission for the inclusion of the provisions on ancestral land (Article VII, Section 5) and regional autonomy (Article X, Section 15) in the new Constitution which was ratified in 1987.

Cory said that many of the demands had to be addressed by legislation, and that a new Constitution still had to be drafted. The CPA then asked for the appointment of a CPA representative to the Constitutional Commission to help draft the provisions for the recognition of indigenous people’s rights in the Constitution. The president agreed to this in front of the whole CPA council. When the time to do so came, however, she reneged on her promise, saying that the CPA endorsee was a leftist. The CPA then had to lobby the Constitutional Commission for the inclusion of provisions on ancestral land (Article VII, Section 5) and regional autonomy (Article X, Section 15) in the new Constitution, which was ratified in 1987.

This was the beginning of a series of Cory’s reneging on her promises. She, in fact, manifested a pattern of betrayal of the indigenous people’s interest. Aquino’s total war policy unleashed the AFP, the pseudo-advocates of IP issues and other political forces.

Martyrs like Ferdie Bragas, Robert Estimada and others were victims of the military, the CAFGU and the CPLA, who were the government’s instruments in its counter-insurgency campaign, harassing and intimidating CPA members and organizers and putting under surveillance local CPA offices.

The CPLA Split and the CEB-CRA-CBAd

Around this time, the Cordillera People’s Liberation Army of Conrado Balweg had split from the CPP–NPA in the region. The CPLA was soon coddled by the Aquino government after the much publicized peace talks and sipat held in Mt. Data in September 1986. On July 15, 1987, Aquino signed Executive Order 220 creating the Cordillera Executive Board (CEB) and the Cordillera Regional Assembly (CRA) as transitional bodies to work towards the creation of the Cordillera Autonomous Region after the ratification of an Organic Act as defined in the Constitution. (July 15 presently is a public holiday in the Cordillera region although only a few seem to know the background to this).

EO 220 gave Conrado Balweg a privileged position as it institutionalized his Cordillera Bodong Administration in the CEB-CRA. Although EO 220 stopped short of official recognition of the CPLA as the regional security force, which it had asked for, the Aquino government practically gave Conrado Balweg and the CPLA license to lord it over the new Cordillera administrative region. Many opportunists soon toadied up to them as they had the power to dispense positions, projects, and patronage in the new structures.

The CPLA even had virtual license to murder and commit criminal acts. In 1987, they killed Daniel Ngayan in cold blood at Cagaluan Gate in Lubuagan. Ama Daniel was a tribal leader from Tanglag, leader of the Cordillera Bodong Association and vice chairperson of the CPA when he was killed. Soon after, they tortured and murdered Romy Gardo of Tubo, Abra, a CPA organizer in that province. Through the years, many others became martyrs through the bloodied hands of the CPLA.

Although Conrado Balweg had the temerity to publicly acknowledge that the CPLA had killed Ngayaan and Gardo, the Aquino government never took him to task for it. Neither was the CPLA punished for their other crimes such as murder, robbery, grave threat and intimidation. The families and friends of the many victims of the CPLA have not yet received any justice from the Philippine government, which had simply tolerated all of their crimes as they were useful in counter-insurgency against the CPP-NPA.

From 1988 to 1993, the CPA had to grapple with organizational problems resulting from Balweg’s split and his eventual distortion, misrepresentation and misappropriation of historical facts and events. His analysis of the Cordillera as a separate nation governed by the bodong system and his proposal for secession and federalism as the forms of self-determination failed to muddle CPA’s correct analysis of Cordillera society. Not a few were misled and co-opted, however. Others were demoralized and opted to be passive. Those were confusing and dreadful times with the CPA targeted for isolation and demolition by both the CPLA and the government.

In December 1999, the CPP-NPA in the region exacted what it called “revolutionary justice,” and killed Conrado Balweg while on a visit to his hometown. In 2003, President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo completed the integration of the CPLA into the Armed Forces of the Philippines.

The CEB-CRA-CBAd lasted from the time it was created in 1987 to 2000. It was composed of a hodgepodge of political appointees, including Conrado Balweg and his CBAd, traditional politicians who probably did not even know what regional autonomy was all about, johnny-came-latelies to the autonomy bandwagon, and a number of former activists.

In the 12 years of its existence, the CEB-CRA-CBAd accomplished nothing of significance. It was just a superfluous structure set up to accommodate political appointees, with all of the graft and corruption, inefficiency and infighting associated with such government bureaucracies. It could not even effectively conduct the educational campaign on regional autonomy that it was mandated to do.

In 2000, Congress practically abolished it by refusing to allocate funds for its operations. The CPA was vindicated in its opposition to these bodies.

Regionalization and Beyond

It is useful to recall one of the early campaigns of the CPA, combining sweeping education, organizing and broad alliance work, which influenced public opinion throughout the region. Many people may not know it, but the Cordillera provinces did not always stand together as one region. One of the early declarations of the dictator Marcos was to divide the Philippines into regions. Without any consideration for the commonalities of history, geography, national minority status and the like, Marcos divided the Cordillera provinces, including Mountain Province and Benguet along with Abra in Region 1, and Kalinga-Apayao and Ifugao in Region 2.

In 1985, the Cordillera representatives to the Interim Batasang Pambansa were trying to pass a bill to regionalize the Cordillera provinces. The CPA allied with the sponsors of the bill for the tactical demand of regionalization but raised the slogan to regionalization and beyond, to be able to conduct a regional campaign on indigenous peoples’ rights and regional autonomy as the form of self- determination for the region.

Bogus Regional Autonomy and the Two Organic Acts

The process towards setting up the Cordillera Autonomous Region defined in the Constitution is for Congress, with the help of a Cordillera Regional Consultative Commission, to draft an Organic Act to establish the autonomous region. The Organic Act shall be submitted to the people for ratification in a plebiscite called for the purpose.

In 1990, RA 6766, the Organic Act to create the Cordillera Autonomous Region was submitted to the people in a plebiscite. It was resoundingly rejected by the voting population in the whole region, except for Ifugao. Again in 1997, a new Organic Act, RA 8438 was the subject of a plebiscite, and again it was resoundingly rejected.

The CPA led the campaign for the people’s rejection of both plebiscites in 1990 and 1997 for a bogus regional autonomy, notwithstanding the fact that it was the CPA that had lobbied for the inclusion of such a provision in the Constitution. The CPA interpreted rejection to mean not necessarily a rejection of the concept of genuine regional autonomy as the form of self-determination in the Cordillera. Rather, the rejection was of the insincerity of government to substantially recognize indigenous people’s rights and genuine autonomy. The Organic Act represented the collusion of central government with the CPLA to co-opt the earlier gains of the mass movement, and exposed the infighting and corruption of traditional politicians and opportunists who had jockeyed themselves into position in the new Cordillera bureaucracy.

The people’s rejection of the two proposed Organic Acts clearly proved the inutility and bankruptcy of the government structures that were merely breeding grounds for graft and corruption.

Anti-Open Pit Mining Struggle

Meanwhile in the late 1980s, Benguet Corporation’s expansive and intensive underground mining operations in Itogon, which started in 1905, had reached its limits. The company turned to bulk mining or open pit techniques. This mode of operation was clearly an outright devastation of the environment, not to mention dispossession of the Ibalois of their ancestral lands, which were covered by mining claims and patents of the mining company. The people’s opposition to BC’s open pit mining operations involved numerous community organizations, small-scale miners associations, women’s organizations, and even the Anti-Open Pit Mining Kids, under the leadership of the Itogon Inter-Barangay Alliance (IIB-A). IIB-A distinguished itself by leading the campaign against open-pit mining during those years, in alliance with the Cordillera Peoples’ Alliance, church groups, NGOs, academe, national environmental groups, and international solidarity friends.

The people expressed their militant opposition through various means and forms: petition-signing, dialogues, community meetings, mobilizations, marches, human barricades and many more. These militant actions were sustained over a period of almost a decade, starting in 1988. The struggle proved successful in stopping the planned expansion by Benguet Corporation of the open pit mines to Barangays Ucab, Tuding and Virac in Itogon. However, the people of Brgy. Loacan were unable to stop the expansion of the open pit to the Camote Vein, when faced with vicious harassment by the company through law suits, arrest and militarization. It was in 1996 that Benguet Corporation halted its open pit mining operations, after exhausting the gold ore in the Antamok Gold Project. They abandoned the open pit mine site, a vast gaping hole, and left behind serious and irreparable damage to the people’s land and livelihood.

Less than a decade later, in 2005, Benguet Corporation ventured into a bulk water project through the privatization and monopolization of Itogon’s natural water sources. The company acquired water rights over numerous natural water springs within its mining claims and planned to use the open pit as a water reservoir. The CPA, together with IIB-A, campaigned against this project. Militant actions in alliance with local government officials and Baguio’s Pro-Consumers movement succeeded in delaying the implementation of the Bulk Water Project and put Benguet Corporation on the defensive.

The Anti- San Roque Dam Struggle

One of President Fidel Ramos’ flagship projects under the Philippines Medium Term Development Plan was the implementation of the San Roque Multi-purpose Dam Project, the third dam to be constructed along the Agno River. Gargantuan funding for the project came in the form of loans from Japan Bank for International Cooperation and investments by corporate interests, including Marubeni and Kansai Electric, with the facilitation of the national government and military backing. This aggression clearly trampled on the Ibaloi people’s right to self-determination.

Reminiscent of the anti-Chico Dam struggle, the Ibalois of Itogon, Benguet put up a sustained resistance, continuing their struggle against the damming of the Agno River, which they had started as early as the 1950s. In 1996, the people of Dalupirip, which was directly affected by the dam, organized the Shalupirip Santahnay Indigenous Peoples Movement (SSIPM) that was at the forefront of the struggle. For several years, the people put up a brave front conducting dialogues, pickets, barricades, rallies, marches not only in Itogon, but in Baguio, Manila, Pangasinan and even in Japan. Broad alliances were forged with the affected communities in Pangasinan as well as with national and international support groups.

The government ignored the people’s protests, and the dam project pushed through, inundating hectares upon hectares of productive agricultural land and displacing gold panners along the length of the Agno River. Now the government is tied down to an onerous power purchase agreement with the San Roque Power Corporation. The government has to pay millions of dollars monthly for the power from the San Roque Dam, whether generated or not.

Even after construction, opposition by the Itogon and Pangasinan people continues – against its burdensome contract and its negative impact on the people, including unprecedented flooding in the Pangasinan plains.

The Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act

In 1998, the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act (IPRA) was passed by the Ramos government as a result of the efforts of various lobby groups and NGOs. The IPRA was hailed nationally and internationally as a breakthrough legislation that would pave the way for the implementation of the constitutional provision recognizing ancestral land and domain rights of indigenous peoples. These were the same provisions that CPA had lobbied for earlier.

From the start, CPA forwarded a position rejecting the IPRA, learning its lesson from the earlier disorientation with the 1987 Constitution. The reject position arose from the need to expose the law as a deceptive instrument of the State and the ruling classes against the people. While seemingly “progressive in form”, in essence, the IPRA co-opted the gains of the indigenous peoples movement and fell short of what it promised. It was clear that the IPRA would never be fully implemented because recognizing indigenous peoples’ rights to land was inconsistent with the interests of the ruling classes and conflicted with other laws such as the PMA 1995. The law also set up the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples that would be instrumental in surrendering ancestral lands to mining and selfish interests.

As time passed, the actual practice of the State exposed the deceptive nature of the law and its utilization to advance corporate mining interests, to disenfranchise IPs of their ancestral lands and to co-opt and pit IP communities against each other. The State manipulated the FPIC provision of the IPRA to facilitate the entry of destructive projects within ancestral lands. The actual experiences of communities with implementation of the IPRA proved CPA’s reject position correct. However, CPA’s critical position on the IPRA did not mean that we could not unite with other groups and political forces that believed in the law based on other urgent issues affecting IPs such as human rights and mining issues.

In 2004, the CPA decided to enter into the process provided by the IPRA for the formation of Consultative Bodies (CBs) from the national down to the provincial level. This was done with the objective of using the process as an opportunity for alliance with other IP groups, raising awareness on IP rights and forwarding the CPA position on various IP issues. On hindsight, there were greater negative than positive results from the experience. One, the CBs should have been seen as part of (not separate from) the IPRA and entering into the process was contradictory to CPA’s position of rejecting and exposing the IPRA as a deceptive law. On the positive side, we were able to gain respect and raise the credibility of CPA while building linkages among other political forces and IP organizations particularly at the regional and national level. On the other hand, we also contributed towards sanitizing and raising the credibility of the NCIP and the CB process, especially as it was the CPA, the militant political center of the Cordillera peoples’ movement, which was involved.

Thirdly, we entered with the illusion that well-meaning IP groups could influence the process from the top down to the provincial level. In the case of the Cordillera Region, this was an over-estimation of the people’s strength and an under-estimation of what traditional politicians and reactionaries would do to manipulate the process for their own political ends.

Continuing Anti-Mining Struggle and Save the Abra River Movement

Aside from the open-pit mining operations of Benguet Corporation, other destructive mining operations are ongoing in the Cordillera, namely Lepanto and Philex. The Lepanto Consolidated Mining Corporation (LCMC) is one seemingly unsinkable giant that has existed for more than half a century in Mankayan, Benguet. The government remains indifferent to the people’s opposition to LCMC’s unabated expansion projects and the extent of destruction it has caused both to land and water resources. The CPA insists that the primary issue is the continued denial of the people’s right to their land and livelihood, while the mining companies are granted limitless access to resources both under and above ground.

Both Lepanto and Philex have been repressive of workers’ demands for just wages and humane working conditions. The people’s swelling anger and defiance erupted in the Lepanto workers’ strikes in February 2003 and June 2005, with strong and sustained community and outside support. These were long drawn strikes, lasting for three months each time, which compelled LCMC to give in to the workers’ demands.

Meanwhile the Save the Abra River Movement or STARM was organized to address the environmental and health issues brought about by LCMC operations all the way along the Abra River from Mankayan down to the Ilocos Region. STARM is composed of NGOs, peoples organizations, academe, scientists, religious groups, professionals and other individuals. The magnitude of environmental destruction and health hazards from LCMC’s toxic mine wastes had reached downstream populations and provinces thus the need for a broader united front through STARM. STARM conducted several environmental investigative missions to the affected areas and exposed the environmental and health problems caused by Lepanto’s operations, earning the ire of the company, the government and the DENR.

At present, more multinational mining giants are poised to plunder the region’s mineral resources at a scale more massive than ever before, facilitated by the Philippine Mining Act of 1995 and the Arroyo regime’s National Mineral Policy. The companies include the Cordillera Exploration Inc. (CEXI) in Apayao, Wolfland Resources Corporation in Kalinga, LCMC’s Far Southeast Mining Project in Benguet, among others. Once again, local communities are on the alert as they vigilantly defend their land and resources from exploration and destruction by mining companies.

Fascist Repression and Operation Plan Bantay Laya

Throughout the three decades of struggle starting in the 1970s, the Cordillera people have been under attack by the ruling administration and its fascist military agents. Militarization intensified during the period of the Chico and Cellophil struggles and continued thereafter in a series of operation plans of the AFP: OPLAN Cadena de Amor and Oplan Katatagan under the Marcos dictatorship; Oplan Mamamayan and Lambat Bitag I and II under Cory Aquino; under President Ramos it was Lambat Bitag III and IV; Oplan Makabayan under Pres. Estrada.

The latest fascist attack under the leadership of GMA is Oplan Bantay Laya, which is a comprehensive 5-year counter-insurgency program aimed at defeating and containing the Muslim and communist movements. The serious concern over Oplan Bantay Laya is that it does not make a distinction between legal, unarmed political dissent from armed rebellion. It does not distinguish civilians from armed combatants. Since the start of the GMA administration until September 2006, there have been 747 political killings and ___ disappearances in the country. Most of the victims were innocent members and leaders of militant mass organizations. Ninety-six (96) of those killed were indigenous people, with 33 killed in the Cordillera during GMA’s rule.

The many years of militarization in the Cordillera have resulted in thousands of cases of human rights violations – killings, bombing, strafing, evacuation, arrest, rape, harassment, and many others. Cordillera martyrs of the struggle, both legal and armed, now number in the hundreds. The latest martyrs of the struggle, killed by military agents just this year, are Rafael “Markus” Bangit and Alyce Omengan Claver.

Campaign for the Defense of Land, Life and Resources

Clearly, all past and present regimes perpetuate national oppression of the indigenous people of the Cordillera. They are consistent in regarding the Cordillera ancestral domain as a resource base, thus the non-recognition of ancestral land rights. They have adopted the twin policies of development aggression and militarization at the expense of the indigenous people’s life and livelihood. The State continues to disrespect indigenous socio-political systems, exacerbating political misrepresentation and commercialization of the people’s culture. Through the years, the indigenous peoples have been victims of institutionalized discrimination and neglect by the State of basic social services. All these are manifestations of the State policy of national oppression and the denial of the right to self-determination leading to ethnocide of the indigenous peoples.

The CPA’s campaign for the defense of land, life and resources continues to meet head-on the agents of development aggression, militarization and imperialist incursion in the region. Community leaders and the CPA are ever vigilant against overtures of multinational corporate lobbyists for mining explorations and operations, construction of mega-dams, hydro-electric projects, logging and other destructive industries.

Augmenting this campaign for the defense of land, livelihood and resources, are sectoral mass movements, addressing the particular issues and problems of the various sectors in the region. Regional sectoral mass organizations have grown in number and strength. These are the militant Cordillera women’s movement represented by Innabuyog; the youth and students movement led by Anakbayan-Cordillera; the workers movement led by Kilusang Mayo Uno – Cordillera; the Cordillera peasant mass movement represented by Alyansa dagiti Pesante iti Taeng Kordilyera (APIT Tako); the cultural workers movement led by Dap-ayan ti Kultura ti Kordilyera DKK); elders organizations like the Bodong Pongor Organization, Am-in and Metro-Baguio Tribal Elders Alliance; the movement of government employees led by COURAGE, the teachers movement represent by ACT, among others. These sectoral organizations have united under the umbrella of the CPA, adding breadth and depth to the Cordillera peoples’ movement.

The CPA is undaunted. The CPA knows its history well. It has drawn precious lessons from the long and arduous people’s struggle. The enemy has evoked from the people the will to resort to legal, meta-legal and even extra-legal means to deliver the point of contention.

The indigenous peoples of the Cordillera were able to fight national oppression against fearsome odds, by asserting their collective human rights to ancestral land and self-determination. In their steadfast and uncompromising defense of their life, land, livelihood and resources, they earned the respect and support not only of other national minorities in the region, but also other progressive forces in the Philippines and abroad.

As it raises high its banner, the CPA forges solidarity with all oppressed sectors in the country and overseas as well. It will continue to play its historical role of arousing, organizing and mobilizing the indigenous people to unite and defend life, land and resources at all costs, until the aspiration for self-determination and national democracy is finally achieved. ***

October 2006

Cordillera Peoples Alliance

(Document as discussed during the CPA 9th Regional Congress held in Teachers Camp, Baguio City)